-

The Problem of the Indian: Revoking Myths and Creating Oppositional Gazes through Pop ArtAlison J. Leedy

It is no surprise now that the influence of popular culture has succeeded in blending high and low art in America. From before and beyond Warhol, artists have utilized countless pop cultural references from Coca-Cola to Michael Jackson and Bubbles, however, one area that needs further evaluation is how art can critique the stereotypes and prejudices that common representation creates. Moreover, what does the definition of pop signify to those who are left outside of popular culture? Do the underdogs have to masquerade as the ruling class, race, gender, religion or sexual orientation to vanquish the attention of the leaders? In Bell Hooks’ controversial critique on how black women have been portrayed in film culture she posits that un-just narratives of power can be revoked through the “oppositional gaze”

-

i.e. the minority control of looking. Hooks states that “…. the ability to manipulate one’s gaze in the face of structures of domination that would contain it, opens up the possibility of agency.”(1) A question then is how to create this freedom of agency in American art when it has been standardized by centuries of Caucasian tastes and ideologies? Furthermore, how are we, as artists, to find new standards of popularity that not only recognize the false and shameful myths surrounding race in our country in the past but also represent the cultural heritage of minority people groups in American art today.

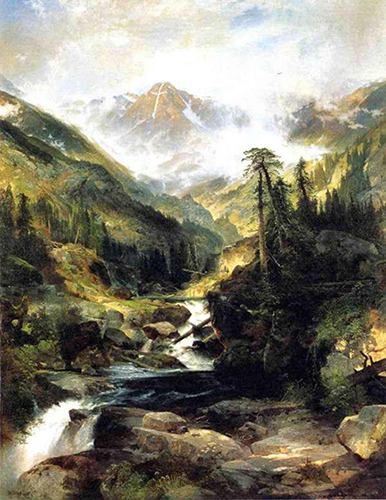

My resettlement last year to Denver, CO brought to mind many dichotomies of what exactly constitutes historical and cultural “American Heritage.” As I pondered what it would have been like to move out west in a rickety wagon two hundred years ago, I thought about the call for In hoc signo vinces (with this sign you will conquer) in Thomas Moran’s and William Henry Jackson’s images of Mt. of the Holy Cross (figs. 1&2). These late 19th century examples of art burgeoned a dream in the minds of many Americans not only of wide-open space and the sublimity of nature but also of manifest destiny.(2) In a recent trip to Santa Fe, I came across Julie Buffalohead’s work at an exhibition at the Santa Fe Museum of Contemporary Indian Art. Buffalohead paints narratives that appear jovial but also blend fact and fiction in a satirical look at the past and present “problem of the Indian” in America. Her work also provokes deeper questions that extend beyond stories of Native American genocide. They also beckon whether old histories can be erased and replaced in the present through creating art that turns the scrutinizing gaze towards the status quo.

Buffalohead is an enrolled member of the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma and comments on her heritage in saying, "My imagery is so personal it's hard to think about the viewer, but I try to be provocative. I use stereotypes because Indians didn't have a

hand in creating them. It's my way of saying, this is not who we are. This is your invention.” (3) Native American artist David P. Bradley, who spent most of his childhood on the White Earth Oijbwe Reservation in Chippewa, Minnesota, also utilizes Pop parody motifs to draw attention to false understandings of his cultural heritage in his Mona Lisa-esque example Pow-Wow Princess in the Process of Acculturation (fig 3). Bradley echoes Buffalohead’s earnestness in saying “ We have an opportunity as artists to promote Indian truths and at the time help dispel the myths and stereotypes that are projected upon us.”(4) The connections between storytelling and xenophobia are unequivocally intertwined with pop cultural trends, being that the definition of the word popular means a “widely held but fixed and oversimplified image or idea…”(5) Incongruously the concept of “fixed” in culture rarely equates to infallibility.

In a masquerade of satirized stereotypes of Cowboy vs. Indian Buffalohead also critiques this juxtaposition through what hypoallergenic magazine refers to as her “theater of animals.”(6) In her work Seems You have to Play Indian to be Indian (fig. 4) she depicts references to pop-cultural understandings of Native American identity with little girls wearing headdresses and a teepee pitched next to a playhouse and a child’s tent that looks like a zebra. One child “playing Indian” is drawing a little red figure on an easel as the other carries a sheave of bow and arrows and stands frozen facing a western cowboy’s pistol. Meanwhile, the “theater of animals” looks on, as they stand exiled from the excitement by a “keep out” sign. The eerie reality of this painting references the land occupation and exile not only of wildlife but also of Native American tribes who dwelled in the Northwest centuries prior to the White man’s arrival and critiques the playful “Cowboy v.s. Indian” romanticism that was projected in hollywood western films of the 20th century.

-

The portrayal of Native American stereotypes in Buffalohead’s paintings not only satirize the exotic myth of the “wild Indian” but also create parodies of reverse pigeonholes hinting at the absurdity of manifest destiny and the “myth of the white man savior.” In her work Christian Falling on a Stick 2014 (fig. 5) Buffalohead depicts a scene where a blonde decapitated Barbie-esque visage wearing a headdress perches atop what looks like a Popsicle stick as a squirrel triumphantly displays his prize to a cowering chipmunk. The inverse positioning of who should be feared in this narrative creates confusion to the viewer as Buffalohead presents the irony of a gentle side of nature that is violently objecting to being tamed.

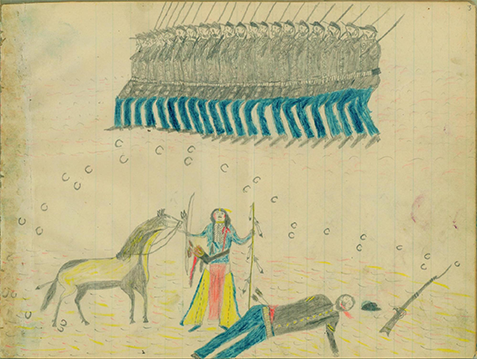

Not only does Buffalohead reverse stereotypes of Native Americans in her work but she also rejects Western principles of classical design. By focusing on reduced forms and colors in a composition rendered with little depth-perspective her work echoes late-19th century examples of Native American Ledger drawings. Ledger paper was given to Native Americans imprisoned at Ft. Marion to occupy their time in internment camps.(7) In the example of Kiowa Indian Ledger Drawing of a Battle with U.S. Soldiers (fig. 6) a lone warrior stands with bow and arrows in hand momentarily victorious over a fallen soldier only to see in the background a blockade of enemy forces. The isolation of the Native American warrior in this image comes from real-life experiences many Kiowa prisoners faced while living in captivity watching their families and tribal culture vanish. The control of Western military forces on the creative and cultural expressions of the Native Americans is present throughout Ledger art and Buffalohead revisits styles and themes from these drawings that successively imparts an “oppositional gaze”(8) for her culture in the present.

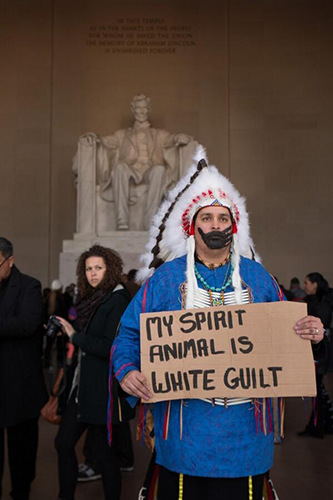

Not unlike Buffalohead, performance artist Gregg Deal asks similar questions regarding contemporary Native American stereotypes in his piece called Last American Indian on Earth (fig. 7). Deal, who is part Native American, literally “plays Indian” in public spaces to draw attention to the contradictions in belief systems about his cultural heritage. Deal often poses in front of popular tourist attractions in Washington D.C. wearing a headdress and holding signs with sayings like “My Spirit Animal is White Guilt” as passer-byes ask to take their picture with a “Real-life Indian.”(9) Standing in front of sites such as the Lincoln Memorial, Deal presents the inherent contradictions that monuments like these on the Washington Mall can represent. For many Americans, wrongs done in the past to African Americans and Native American Indians have been made right and stone sculptures laid out in front of reflecting pools by day and dazzling colored lights at night are there giving fortified proof of freedom for all. Deal’s work presents another side to this story that asks whether these monuments really take the place of lives lost or are they just token symbols of a guilty nationalist conscience? The physical presence of Deal next to a monument representing freedom and justice for all echoes the words of Native American activist Jimme Durham “They didn’t see that we lost because they never see us at all.”(10) Moreover, not only does this work revisit the missing pieces of Native American traumatic history but it directly applies to their forgottenness as people living in the present.

Bell Hooks’ idea of the “oppositional gaze” presents an answer to the problem of forgottenness of black women in White cinema, and not unlike Hooks, Buffalohead uses art to satirize the roles of Native Americans created in western novels and films.

-

Critiquing these stereotypes also creates an opportunity to pivot towards more authentic images of Native Americans living and creating art in the present. Only when the art world allows for styles of those outside the dominant western art historical cannon to exist as they are, and not as imitations of western art, will narratives of injustice be re-written and a diverse counter-culture co-exist beside popular cultural trends. Consequently, creating socio-political and cultural space for individuals to live beyond acculturation and retain linage to their “outsider” beliefs is when an understanding of American Heritage is no longer unilateral. ⊗

(Fig. 1) Thomas Moran, The Mountain of the Holy Cross, 1875, oil on canvas, 7'x5', National Gallery of Art, D.C.

-

(Fig. 2) William Henry Jackson, The Mountain of the Holy Cross, 1873, stereoscope.

(Fig. 3) David P. Bradley, Pow-Wow Princess in the Process of Acculturation, 1990, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 36″ Plains Art Museum, Fargo, ND.

-

(Fig. 4) Julie Buffalohead, Christian Falling on a Stick, 2014, acrylic, ink and graphite on lokta paper, 12 3/8 x 15 ½, Bockley Gallery, Minneapolis, MN.

(Fig. 5) Kiowa Prisoner, Kiowa Indian Ledger Drawing: Battle with U.S. Soldiers, 1880, pencil on paper, Newberry Library, Chicago.

-

(Fig. 6) Julie Buffalohead, Seems You have to Play Indian to be Indian, 2010, missed media on paper, 50.8 x 81.3 cm, Bockley Gallery.

(Fig. 7) Gregg Deal, Last American Indian on Earth, 2014, performance piece, Washington Mall, D.C. http://greggdeal.com/The-Last-American-Indian-On-Earth

-

Bibliography

Bockley Gallery. “Julie Buffalohead.” Accessed November 1st, 2015.

http://bockleygallery.com/artist_buffalohead/index.htmlBoyer, Paul S. “Manifest Destiny,” In The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Cornado, Kris. “Last American Indian’ finds challenges in performance art,” The Washington Post, February 14, 2014.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/last-american- indian-finds-challenges-in-performance-art/2014/02/13/08b88100-82ba- 11e3-8099-9181471f7aaf_story.htmlHooks, Bell. “The Oppositional Gaze,” In Black Looks: Race and Representation. New York: South End Press, 1992.

Layson, Hana and Norby, Patricia Marroquin. “Art of Conflict: Portraying American Indians 1850-1900,” The Newberry Library Digital Collection. Accessed November 1st, 1015.

http://dcc.newberry.org/collections/art-of-conflict-portraying-american-indiansPapastergiadis, Nikos and Turney, Laura. On Becoming Authentic: Interview with Jimmie Durham. Cambridge: Prickly Pear Press, 1996.

Plains Art Museum. “David P. Bradley.” Accessed November 1st, 2015. http://plainsart.org/collections/david-p-bradley/

“The Truth About Stories: Julie Buffalohead.” Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, May 30-July 31, 2015. Santa Fe, NM.

COMMENTS

ALSO THIS ISSUE

The Problem of the Indian

In The Hour of The Wolf

Falling in Love with the Idea of Her

Accepting the Spoilers

The Moment I Finally Fell for Dawson’s Creek

Angela’s Ashes

Redressing Showgirls

MONSTER JAM™ / MILK JUG

Images for Earth Day

Riding with Lana Del Rey and Courtney Love

The Greatest Artist of the 20th Century