The Good Search: Iggy Donnelly and the Eternal Philadelphia Return

By SUZANNE SEESMAN

Posted: 7/8/11

When it evokes him at all, popular memory usually remembers Ignatius Donnelly as a kook, a half crazy schemer and a bumbling pseudo-intellectual who got all sorts of things wrong. The only stalwart reverence remaining for him today is kept alive by a subculture of occult followers who still consider his works to be the on-point musings of a genius and a prophet. Over the past couple decades, a hand full of essays and one book have cropped up to fill out and complicate our thus far limited collective memory of the man. For the most part, these writings come down on one side or another of that dependable ol’ love/hate divide. Regardless of present day opinions, many of Donnelly’s ideas reverberated throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. His impact can be found as much in the sandy soil grounding conspiracy theories as it can in the bedrock of respected scientific theory, fiction writing, alternative economics, and political justice movements throughout his time and ours. While most of his great ideas may have ultimately faltered, Donnelly’s advocacy of them never did. Ignatius, Iggy to his friends, was a survivor and a full on Destiny’s Child style not-gonna-give-upper. I was an independent on the Donnelly appreciation question, gravitating toward third party platforms. What interests me most about the man is not the efficacy of his ideas but his persistence to keep up the good search.

In the spirit of summer, I decided to follow a diversion from my usual research to delve into the depths of this man’s life and legacy. Donnelly was known as a Minnesotan but he was a South Philly boy born and raised. In wading thorough the small sea of information about him, I ended up on the shores from whence he came to see if I could find the secret to his inspired dedication.

The dim lighting and cold air of the of the Pennsylvania Historical Society’s microfiche room had made me drowsy. I was dressed for biking through the humid heat of an urban east coast summer’s day but I had been sitting for almost three hours in the cool institutional air conditioning. Between yawns, I invented a ritual in attempts to combat the lethargy, a practice where I would turn the handle of the manual microfiche machine back at a pace that would sync the click and rhythmic sound of the machine to the images on the screen. As the black and grey lines streamed vertically past, my eyes fell gently in and out of focus, and I concentrated on the repeating resonance of the film strip catching for a moment on the mechanism and then sliding back onto the spool. While the width of the bars expanded and contracted, peripheral marks-fuzz and other marginal occupants, contextualizing notations, postdates, expository remarks- flicked by, punctuating the abstract composition.

I convinced myself that by transforming the material into a discrete work of experimental film, I could somehow undo a bit of the eye and brain strain that my needle-in-a-haystack research caused. It was my third visit to the Society but my first to the microfiche room. By the end of the second roll, my jaw was tight and the pressure building in the small muscles around my cheek bones had stretched into the tissues behind and around my eyes.

After hours of sifting through these documents my mind had started to wander to other times and places. I imagined the moment in 1839 that John Benjamin Dancer invented the microfilm. With a ratio of 160:1, I visualized all the world's eyes inexplicably squinting for a brief moment as he placed the final touches on his patent drafts. The piece of information I was looking for among these files dated back to, roughly, the same era as the era of microfilm's invention. I was in pursuit of the Philadelphia home address of one: Ignatius Donnelly.

At this point, I had arrived at Frame No. 81 of Roll 2 in the collection titled “The Ignatius Donnelly Papers”. My chances of finding the address were grim for this frame was filled nearly to the edge with an image of the blueprint outlining the grounds of Donnelly’s estate at Nininger. A community on the banks of the Mississippi in Minnesota, Nininger was to be an idyllic place. The record of Donnelly’s investments showed that he dedicated his money to educational and beneficent institutions. This slide, No. 81, shows the plans for his personal home embedded in the larger Eden that he had envisioned. The grounds of his personal estate are represented here by two wide light grey circles converging into a cluster of three rectangles over a field of dark gray with detailing in a still darker charcoal tone. This design looks both archaic and modern: something between a Judd or Lewitt drawing and a turn of the century newspaper illustration from the world’s first report of a crop-circle sighting. Compared to the other maps in his files this one is understated, minimalist.

These shades of grey on the old slide match today’s satellite view of the same grounds. From a far zoom on Googleearth the the land looks like olive grey and dark taupe plots of wormwood. This striking frame of film signaled me to turn around. I knew that this image marked the finalization of the plans for Donnelly’s move to Minnesota and that there was not much point in moving ahead. Yet I paused for a moment and I continued scrolling forward for bit before turning back. Sure enough, in the following frames, Nos. 82-87, all signs of Philadelphia life slip away and notes and receipts begin to bear Minnesota markings.

When the bottom fell out of the funding for Nininger City, Donnelly’s plans for a public school, a civic reading room, an atheneum, and a lyceum failed to come to fruition. Despite the very public failure of his big dream, Ignatius Donnelly stayed the course and made his Nininger estate his home until the end of his life over forty years later. It was from this home, in the middle of the intentional community that never was, that he made his career as a Congressman, a populist speechmaker and a rabble-rouser. Since it was also from this outpost along the banks of the Mississippi River that he wrote all of his books, it makes sense that most of the information about his life revolves around his time in Minnesota but it was making my work more frustrating. No matter how hard I looked, I wasn’t finding any information on his residences in Philadelphia. While I wasn’t finding what I was searching for, I was coming to understand the man’s character in much greater depth. His records showed the complexity of his thinking and the hopefulness that pervaded all his plans. While he kept extensive and organized records, there were bracketed anomalies in his organizing system. Intermittently and inexplicably filed among countless ledgers, business transactions, correspondences, and beautifully lithographed receipt slips were haphazard items: a magazine article on a Mesozoic-American archaeological dig, populist party pamphlets, writings on love, quixotic musings about friendship and poems on citizenship.

At the core of Donnelly’s character is the conflation of the ideal with the entrepreneurial and the social with the economic. From the most comprehensive text, Martin Ridge’s 1991 book, Ignatius Donnelly: The Portrait of a Politician, to the briefest, an entry in American Social Leaders and Activists by Neil A. Hamilton, to the top Google result, the Ignatius Donnelly entry in Wikipedia, his biographers describe him as a progressive politician, an amateur scientist, and a social planner with audacious ambitions and Utopian dreams. His idealistic stance is also obvious from his own writings. In Atlantis: the Antediluvian World, he uses the description of the lost continent set forth by Plato in “Critias” and spins it out into a complex of conjecture that ties together geographic, political, and historical features of the current world. In Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel, his observations of the cracks in the earth of the Great Lakes lead him to surmise that a catastrophic meteor was the cause of most of earth’s major geographic features and the basis for the majority of the worlds cultures and religious beliefs. While he took extremely progressive stances on most issues, he was, like most politicians, guilty of hypocritical contradictions as well. He advocated for progressive causes from women's rights and the abolition of slavery to better working conditions on the one hand while simultaneously working to displace the Sioux Indians of his home state on the other.

The microfiche records reflect these knowns about Donnelly's character, while it also reveals facets of the man’s personality that most biographers miss entirely or, at least, play down. Among the records interspersed in his financial records are groups of correspondences between Donnelly, his wife, their friends and their colleagues. These letters expose a thoughtful, a self-reflective, and a, at times, even self-doubting man. The biographers with a more negative outlook on his personality, portray a bumbling, irrational or inexcusably and tragically naive character blinded by his own ego. Some, like Charles P. Pierce author of Idiot America: How Stupidity Became a Virtue in the Land of the Free who points out Donnelly’s punditry, go so far as to call him an anti-intellectual. Even his fans, who take a more positive bent in describing his personality, still present him as ego driven, overly opinionated and brash. While I don’t deny that the man clearly seems to have had a hot head and an inflatable ego, it seems to me that these characteristics did not make up the connective tissue of his Achilles heal.

To me his introspection seems outweighed not by his ego but rather by his boundless optimism. His confidence in the future was a type that is based on an enduring belief in an idyllic past. He trusted the unifying clarity that an eternal return could provide.

It is clear from his papers that after moving his family to Nininger, Donnelly intended to never look back. But the language of his plans for Nininger show that this was not out of an aversion to the nostalgic. Donnelly was, in fact, clearly invested in looking back, just not to his own past. He craved another more distant past. In the nomenclature he choose for labeling his monetary contributions to the building of Nininger City, one can see in which history preoccupied his mind. He had set aside money for an antheneum and a lyceum rather than setting aside funding for a reading room or a public lecture hall. More informal terms like these latter, I suspect would not have worked for because they would not have implied any connection to Classical Athens. Donnelly wanted to point to a legacy that was unlike his upbringing in suburban Philadelphia. His focus when looking back was on an idyllic past inaccessible to him except through study and imagination. Ignatius, was following Plato’s lead imagining a golden era long lost but somehow still attainable. However, while there is reasonable support for an argument that Plato deployed ideal visions like the one he set fourth of Atlantis in the book “Critias”, as rhetorical devices -ideals which one might hold up to the real for consideration, comparison and contemplation- there is little doubt that Donnelly was anything but wholeheartedly literal about his postulations.

It is possible that his faith in a cohesive future based on a golden past could be a result of the time in which he lived. He was born into a South Philadelphia Irish immigrant family in November of 1831. The first years of his life unfolded during the decade that would see the popularization of such extreme innovations as photography, as well as the use of now seemingly banal things like the term “scientist” (1833) and the postage stamp (1837). Everything he did took place against the backdrop of the windup to the twentieth century. He lived in an era with an ethos of hope and change that would make even Obama’s most earnest speechwriter uneasy today. And Donnelly didn’t just come of age in these times, but he exemplified them. His life seemed to be entirely focused on anticipating the twentieth century. This theme even structured his death. In a poetic fashion that he could not have planned, Ignatius Donnelly died on January 1, 1901, just in time to live through the turn of the century but not a day longer.

His optimistic propensities fell in line not only with his era, but also very much with his nationality. Donnelly was an American style dreamer and doer in the tradition of forefathers before him like Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin. Like Jefferson, he was a voracious reader, an independent scholar, a would-be community and urban planner, an amateur scientist and a farmer. Like Franklin, he was a writer and social commentator with working class roots. Donnelly was educated at Philadelphia’s Central High School, one of the nations first public schools, and came to prominence in the Philadelphia establishment through work rather than pedigree. Following his predecessors of an earlier century, he became a politician and a public speaker of note whose orations crossed disciplines that were not yet established or defined.

Because of his pan-intellectual ambitions Donnelly is often called a Renaissance man, but where this term is an appropriate attachment to the Francophile Jefferson or to the dedicated logician Benjamin Franklin , it seems to me an uncomfortable term to assign to Donnelly. While Ignatius was a polymath styled after these famous progenitors, he was of a slightly different and decidedly more modern ilk. “Iggy” was a westward-gazing, starry eyed, North American who led more with his heart than his brain and who hoped to make the real conform to the ideal rather than the other way around. The ideal Renaissance man would have admired Donnelly’s desire to be the genesis of his own knowledge but would have likely frowned at his flagrant disregard for objectivity. A “Renaissance man” would never wear as much on his sleeves as Ignatius Donnelly did. In this sense, his style was very new world. He was a kind of a pre-Rooseveltian American politician as ruddy and charismatic as Teddy would be, and as socially conscious as Franklin.

My search for Donnelly’s origins started with a tangent. An off shoot from an internet search for texts on the role of myth and metaphor in Plato's dialogues that spun out of control. The search became a bout of information overload, one of those time-sucking events leading to every which way but clarity. When the session was all over, I was left with the Plato inspired endeavor that Donnelly is best known for today, which is the authoring of Atlantis: the Antediluvian world. Aside from Donnelly’s general admiration for Classical Greek civilization and culture, Plato, it seams, was important to him for the same reason that he is interesting to me. Plato combines the metaphorical and the expository, he blurs the line between the ideal and the historical and he unites the scientific with the allegorical.

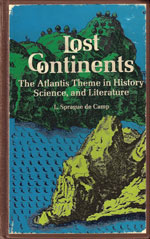

In order to test the metal of our kindred spirit-hood, and also to take a break from the more heavily philosophical texts, I went to the library to pick up a copy of Ignatius Donnelly’s most famous book only to find that it was not there. While Temple University’s “Diamond Catalogue’ said that it, GN751.D68 1949, was available, there was no sign of its existence on the shelf. There was not even the sign of a gap between The Atlantis Researchers and Lost Continents.

Here-forth I had become more interested in Donnelly’s life than in his text. And I had, in any case, discovered that the missing book was available online, along with most of his others, in it's entirety. So instead of looking for the books he authored, I went in search of Ignatius Donnelly: The portrait of a Politician by Marin Ridge, the only comprehensive biography on the man. This book was not on the shelf either. In the place where it should have been all I found was a strange punch card,

If I could not find what I was looking for in the library, I would have to move my quest elsewhere. I went to the Pennsylvania Historical Society with the idea that a visit into the belly of the local history beast might dramatically change my game. Having discovered that Donnelly was born and raised in a Philadelphia suburb that technically no longer exists, I thought someone there might be able to point me in the right direction. His birthplace, Moyamensing, was subsumed by the city proper in a bout of late nineteenth century urban sprawl and I was having trouble online trying to figure out exactly where Moyamensing had actually been. I was becoming more and more intent on finding out where exactly Donnelly launched the ship of his epic life journey from.

When I arrived I went directly for the Society’s reference reading rooms and pulled out two copies of McElroy's Philadelphia Directory: one from 1848 and the other from 1850. In the 1948 edition, the entries for the name Donnelly found on pg 90 are as follows:

Donnelly Hugh, clerk, 20 Bank

Donnelly Hugh clerk, 402 S 2d

Donnelly James, coal, 14 Rittenhouse

Donnelly James, labourer, Baker n Sch 4th

Donnelly James cabinrtmr., 62 Apple.

And the entries in the 1850 edition on pg 105 are similarly unhelpful helpful and as follows:

Donnelly Hugh , clerk 3d and Wesley

Donnelly Hugh, lab. Dorothy ab Sch 4th

to

Donnelly James, bootmr.Sch 8th bel Ogden

Donnelly James cabinetmr. 305 Cedar

Donnelly James lab. Ashton n Pine

Donnelly Jas., weaver, Murray n Sch 2nd.

with no sign of Ignatius

Because he was not to be found in the Library nor in these Directories, I differed to the Society’s card catalogue collection of citizenry. There, I was elated to finally see his name in physical print penciled onto one card in the Dom-Doph drawer. I took down the information on the card and recopied it moments later onto a resource request form. I took the form to the file librarian and sat down to wait. About eight minuets later, the file clerk appeared at the desk with a thin light manila folder. The contents of the file were only three sheets of paper. The folder was sparse and inconsequential to my search. Two of the sheets of paper therein bore a letter about his estate and the third, a larger more yellowed sheet, had a printed vignette style portrait. I skimmed the letter, returned the file and left the building. The next day I stopped in again, but gleaned even less information in the short time I had there. On third visit though, I began my search by speaking with a very helpful librarian who shared my interest in Donnelly. He told me that sometime in the mid 1980s the Pennsylvania Historical Society had acquired a copy of the Minnesota Historical Society’s microfiche collection of Donnelly’s papers.

I had been looking in all the wrong places but was now headed in the right direction to the microfiche room. I immediately, pulled several rolls of this prodigal microfilm from the drawer and sat down at one of the looming giants of 1970s microfilm display. Within several hours I was at the very edge of drowsy disillusionment in the chill of the midsummer’s morning air-conditioning.

Thinking that I had lost the search again and maybe finally for good, I breathed deep and tracked the flecks of my abstract film creation. Then, like a bolt, the realization came cutting through my half-dreaming brain. I had been so mindless! I had been so convinced that the information was impossible to find that I had overlooked it entirely. I was now cranking steadily back through the reel letting it wash over me without stopping. The key to my search and the answer to my ever increasingly urgent question was right there on the roll.

I stopped scrolling, turned the real back several frames, narrowed my eyes and turned my head to the side. It was in the notes, in the postscript. There were addresses in the margins and in the intermittent pages.

There had been few envelopes accompanying the correspondences and only some of the letters were marked with few addresses at the top or in the body. But someone, perhaps Helen McCann White, the author of The Guide to Microfilm Edition of ‘The Ignatius Donnelly Papers’, her assistant or any number of the Minnesota Historical Society predecessors had penned in the missing information. I was glad for the diligent person who put the information there. I scrolled back to the Philadelphia days and eyed these notes. I found an address and then another and then another. The recurring address “No.108 Walnut St.” was most likely to be a business rather than a home address, but the one on Spruce was very probably residential. It had no specification and I could not tell if the correspondences before and after it fit more securely into business or social correspondence. I wrote it down anyway and since I could not figure out if the last number was a 0, 2 or 7, I had three versions of the address from the year 1855. I hurried back over to the reference section for if Donnelly had held business on Walnut St., which was surely part of Philadelphia proper in the mid 1850s, then he should be able to be found in one of the Directories.

I pulled out the 1856 edition of A.M. Elroy’s Philadelphia Consolidated Directory and flipped to the “Donn” section.

There he was....

Donnelly Ignatius atty&coun 108 Walnut h. 222 Spruce

tucked in the space between

Donnelly Brideget, Phoenix bel Parry (K.)

and

Donnelly Chas., weaver, Caldwalader ab Master

I quickly put everything away, grabbed my bag from the locker and headed out the door. I stopped by my house, dropped my bike, threw on some running clothes and headed east. When I came to the 200 block I slowed to a walk and started looking at the numbers. The street was lined with brownstones with the exception of one. Number 222. It was a butter cream yellow wood paneled colonial house facing spruce and rounding the corner of a cobble stone ally. My brain was pulsing and my face was radiating heat as I stared at the house. Breathing heavily, I crossed the street hoping to find a sign in the window reading something like, “Resident: Ignatius Donnelly Lawyer, Politician and Dreamer”. And this would either be preceded by or followed by the name of the carpenter. But there was no such sign. I rounded the corner to the cobblestone ally to see if it was on one of the windows facing the ally but there was no label there either.

I stood in the tiny street lined with Irish and colonial American flags feeling confused. I had arrived at my destination but I couldn’t stop searching. Unsure of what I had expected from the place, I began to realize that there was no way for me to know if this had ever been his house at all. What if over time the addresses had shifted? It seemed “original enough”. I was realizing that my search was just as naive as any of Donnelly’s. I begin to think about how sure I had been, while sitting in the Historical Society, that this sight would give me some sense of Donnelly’s inspiration. I suppose I had expected to be able to bask here in his motivation absorbing it along with heat of the summer sun. As I examined the the eroded brick path , I realized that I had been looking for something that was inaccessible. I was on my own imperfect journey of eternal return hoping to gain something in return for all my desire but was left with worn stones beneath my feet.

The introduction to Donnelly’s book, Caesar’s Column, is titled “To The Public”, and reads:

“The world, today, clamors for deeds, not creeds; for bread, not dogma; for charity, not ceremony; for love, not intellect.

Some will say the events herein described are absurdly impossible.

Who is it that is satisfied with the present unhappy condition of society?"

I suppose I was looking for the wellspring that inspired such visionary sentiment. The source that sent him along on his relentlessly hopeful journey and that kept him believing despite the realities he was faced with. Like the romantic myth of Atlantis though, the provenances of Donnelly’s inspiration are now traces: illusive vestiges of a bygone golden age. His story though is, like Atlantis, still a good one to retell. His idealistic outlook might not fit with my reality but in a culture dominated by stifling incredulity and overwrought appreciation for even the weakest of ironies, his is a great example of what was once possible for another person in another place and time. When I allow my own penchant for cynicism to get in the way of my intellectual imagination, I will have his story to revisit for consideration, comparison and contemplation.

|

|